When one thinks about the fate of Kriegies in German captivity, one often reads that their chief problem was their fight against boredom and “the wire disease.” However, food shortages constituted an equally pressing problem. German officials-- especially in a blockaded and increasingly devastated Third Reich--did not view the nourishment of their ever-growing number of POWs as a priority. Though the Germans did not starve the Allied POWs--as was the case with Soviet prisoners of war, of whom over 3 million perished in German captivity-- the quantity and quality of the food they supplied to the Stalags and Oflags was sub-par to say the least. Former Kriegies later recalled how shocked they were to be served a piece of ersatz bread made of sawdust and flour or a watery soup cooked with maggoty horse meat and a meagre amount of rotten vegetables.

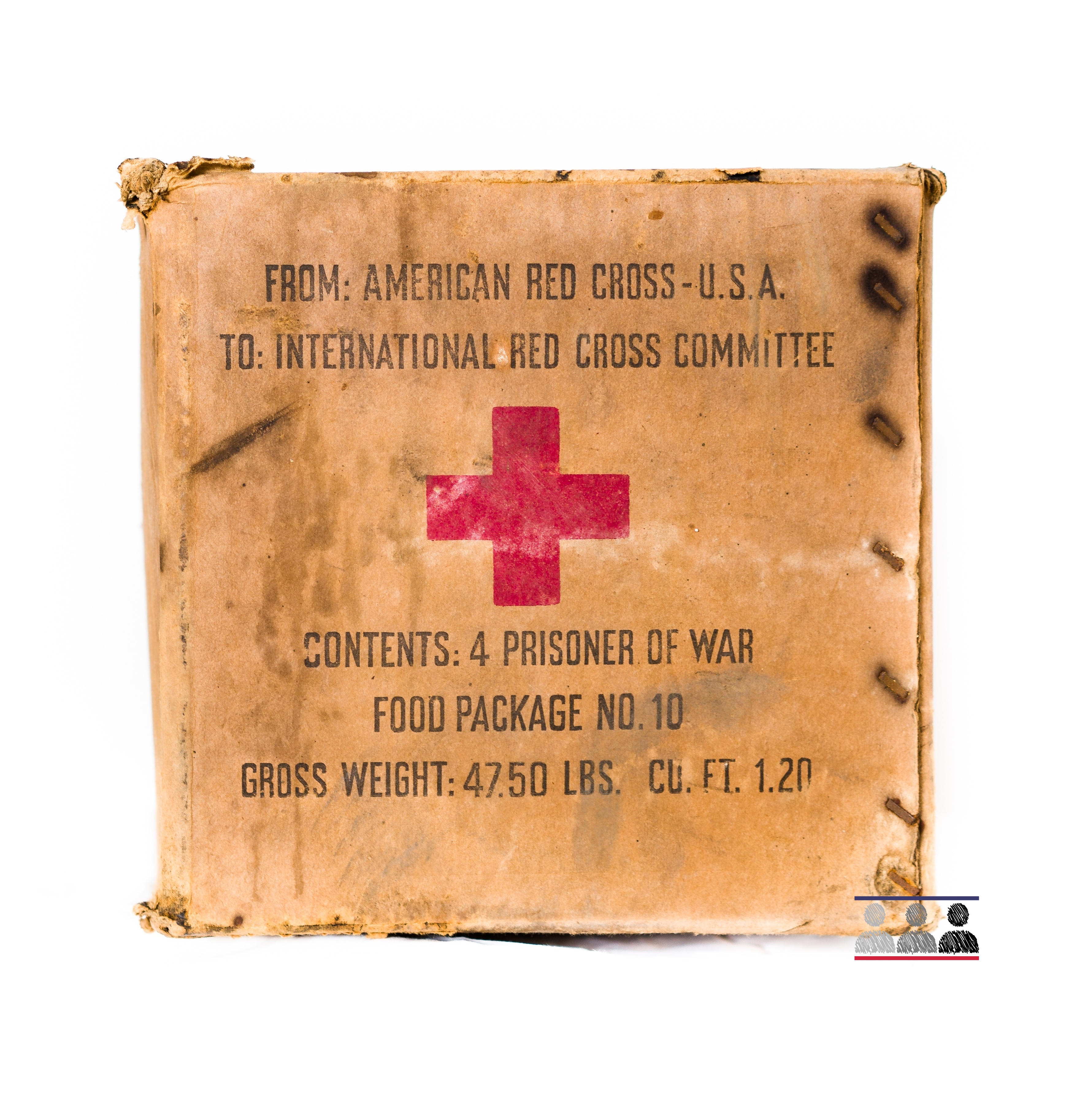

Luckily, however, the Germans mostly adhered to the Geneva Conventions on the Treatment of Prisoners of War and, as had been stipulated by the treaty, allowed Allied nations’ aid organizations to deliver supplemental food and supplies. The International Red Cross was one such designated organization, and supervised the packing, transport, and distribution of parcels to the POW camps across Nazi Germany. On average, a prisoner of war could expect to receive one Red Cross package every week. Often, however, the number of delivered parcels was not sufficient, and so the Kriegies shared.

A typical parcel contained tinned foods, like jam, tuna, condensed soup or powdered milk; packages of sugar, raisins, coffee or biscuits; sweets in the form of chocolate bars or cookies; plus every-day essentials like soap; and, most important for many, cigarettes. In addition, some parcels included basic medical materials, which helped camp doctors keep their wards reasonably healthy.

In most camps the prisoners donated a portion of their food ‘luxury’ items to the POW kitchen “pantry” so that the POW cooks could combine them with the standard German rations and create something more edible. Other pooled items-- like cigarettes-- were especially treasured, as the Kriegies used ‘smokes’ in lieu of currency. Those precious few who didn’t smoke were the luckiest, as they could barter their extra cigarettes for special services or other craved delicacies.

To maintain the lifeline provided by the Red Cross parcels, Allied military authorities worked to ensure that no clandestine organizations used Red Cross packages to conceal escape aids. If the Germans had discovered such a scheme, they would have immediately halted the distribution of all parcels.

Red Cross parcels maintained the morale of the Kriegies, not just because of their precious food and supplies, but also because they represented tangible proof that the home country had not forgotten their men in captivity. Along with mail from home, these parcels kept the POWs from becoming despondent. Sometimes the parcel contents contributed to the POWs holiday celebrations, such as Thanksgiving or Christmas, like when the Red Cross thoughtfully included tinned turkey meat.

Whenever the inflow of the packages stopped—such as during the relocations of various camps due to the advancing Red Army--the POWs’ health deteriorated rapidly. In the last months of the war, when Allied bombings paralyzed Germany’s transport, and the Germans relocated and concentrated many prisoners in makeshift camps, General Eisenhower even arranged to use American lorries for emergency shipment of the parcels.

Overall, the American Red Cross produced more than 27 million packages during WWII and the British Red Cross contributed more than 20 million. Many parcels were also sent to the inmates of the notorious Nazi concentration camps, where the conditions were incomparably worse than in the POW camps. According to some of the survivors, Red Cross packages were the difference between life and death in these camps.